Laplace Transform

Sources:

- B. P. Lathi & Roger Green. (2018). Chapter 4: The Laplace Transform. Signal Processing and Linear Systems (3rd ed., pp. 330-404). Oxford University Press.

Laplace Transform

The Laplace transform is a mathematical operation that converts a time-domain function \(x(t)\) into a complex frequency-domain representation \(X(s)\).

Notation

| Symbol | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| \(x(t)\) | Function | Original time-domain signal |

| \(X(s)\) | Function | Laplace transform of \(x(t)\) |

| \(s\) | Complex number | Complex frequency variable, \(s = \sigma + j\omega\) |

| \(\sigma\) | Real number | Real part of \(s\), representing growth/decay rate |

| \(j\) | Constant | Imaginary unit, \(j = \sqrt{-1}\) |

| \(\omega\) | Real number | Imaginary part of \(s\), representing angular frequency |

| \(u(t)\) | Function | Unit step function |

| \(t\) | Real number | Time variable |

| \(\mathcal{L}[x(t)]\) | Function | Laplace transform operator applied to \(x(t)\) |

| \(\mathcal{L}^{-1}[X(s)]\) | Function | Inverse Laplace transform operator applied to \(X(s)\) |

| \(\operatorname{Re}(s)\) | Real number | Real part of \(s\), used to determine the region of convergence (ROC) |

| \(\operatorname{ROC}\) | Set | Region of convergence for \(X(s)\) |

| \(\sigma_0\) | Real number | Abscissa of convergence, the smallest \(\sigma\) for which the transform exists |

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|

| ROC | Region of Convergence |

| LHS | Left-Hand Side |

| RHS | Right-Hand Side |

Bilateral Laplace transform

The bilateral Laplace transform of a function \(x(t)\) is defined as:

\[ \begin{equation} \label{eq4_1} X(s) = \color{blue} {\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} } \color{red}{x(t)} \color{green}{e^{-s t}} \, \color{violet}{dt} \end{equation} \]

where \(s\) is a complex variable ( \(s=\sigma+j \omega\) ) that consists of a real part \(\sigma\) and an imaginary part \(\omega\).

Convergence of the transform

Note: In this context, we consider absolute convergence rather than regular convergence. For a given \(s\), the integral \[ \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} x(t) e^{-s t} d t \]

may fail to converge absolutely, meaning the integral

\[ \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\left|x(t) e^{-s t}\right| d t \]

does not evaluate to a finite value. When this happens, the Laplace transform does not exist for that specific \(s\).

The region of convergence (ROC) defines the set of values of \(s\) for which the transform converges absolutely and therefore is well-defined. A detailed discussion of the ROC is provided in a later section.

Inverse Laplace transform

The inverse Laplace transform retrieves \(x(t)\) from \(X(s)\) and is given by:

\[ \begin{equation} \label{eq4_2} x(t)=\frac{1}{2 \pi j} \color{blue} { \int_{c-j \infty}^{c+j \infty}} \color{red} {X(s)} \color{green}{e^{s t}} \color{violet}{d s} \end{equation} \]

where \(c\) is a real constant chosen such that the integral converges. This equation forms the basis for reconstructing the original time-domain function from its Laplace transform.

Bilateral transform pair

The pair of equations for the bilateral Laplace transform and its inverse are often written symbolically as:

\[ X(s)=\mathcal{L}[x(t)] \quad \text { and } \quad x(t)=\mathcal{L}^{-1}[X(s)] . \]

These equations satisfy the following properties:

\[ \mathcal{L}^{-1}\{\mathcal{L}[x(t)]\}=x(t) \quad \text { and } \quad \mathcal{L}\left\{\mathcal{L}^{-1}[X(s)]\right\}=X(s) \]

It is common to use a bidirectional arrow to indicate a Laplace transform pair:

\[ x(t) \Longleftrightarrow X(s) . \]

Region of convergence

The region of convergence (ROC), also called the region of existence, for the Laplace transform, \(X(s)\), is the domain of \(X(s)\), i.e., it is the set of values of \(s\) (the region in the complex plane) for which the integral in \(\eqref{eq4_1}\) absolutely converges. For \(s\) outside of ROC, \(\eqref{eq4_1}\) does not converge, making \(X(s)\) undefined and meaningless.

Example: Laplace Transform and ROC

Consider the signal \(\color{salmon}{x(t)=e^{-a t} u(t)}\). Let's find its Laplace transform \(X(s)\) and the corresponding ROC.

Solution

By definition of the Laplace transform:

\[ X(s)=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-a t} u(t) e^{-s t} d t \]

Since \(u(t)=0\) for \(t<0\) and \(u(t)=1\) for \(t \geq 0\), this reduces to:

\[ X(s)=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-a t} e^{-s t} d t=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-(s+a) t} d t \]

Evaluating the integral:

\[ X(s)=-\left.\frac{1}{s+a} e^{-(s+a) t}\right|_0 ^{\infty} \]

Here, the convergence of the term \(e^{-(s+a) t}\) as \(t \rightarrow \infty\) depends on the real part of \(s+a\)1. Recall that for a complex number \(z=\alpha+j \beta\) :

\[ e^{-z t}=e^{-(\alpha+j \beta) t}=e^{-\alpha t} e^{-j \beta t} \]

The magnitude \(\left|e^{-j \beta t}\right|=1\) regardless of \(\beta\), so \(e^{-z t} \rightarrow 0\) as \(t \rightarrow \infty\) only if \(\alpha>0\).

Consequently: \[ \lim _{t \rightarrow \infty} e^{-z t}= \begin{cases}0 & \text { if } \operatorname{Re}(z)>0 \\ \infty & \text { if } \operatorname{Re}(z)<0\end{cases} \]

Applying this result, we find:

\[ \lim _{t \rightarrow \infty} e^{-(s+a) t}= \begin{cases}0 & \text { if } \operatorname{Re}(s+a)>0 \\ \infty & \text { if } \operatorname{Re}(s+a)<0\end{cases} \]

Thus, the integral converges only if \(\operatorname{Re}(s+a)>0\), giving:

\[ X(s)=\frac{1}{s+a}, \quad \operatorname{Re}(s+a)>0 \]

or equivalently:

\[ \color{salmon} {x(t) \Longleftrightarrow \frac{1}{s+a}}, \quad \color{red}{\operatorname{Re}(s)>-a} . \]

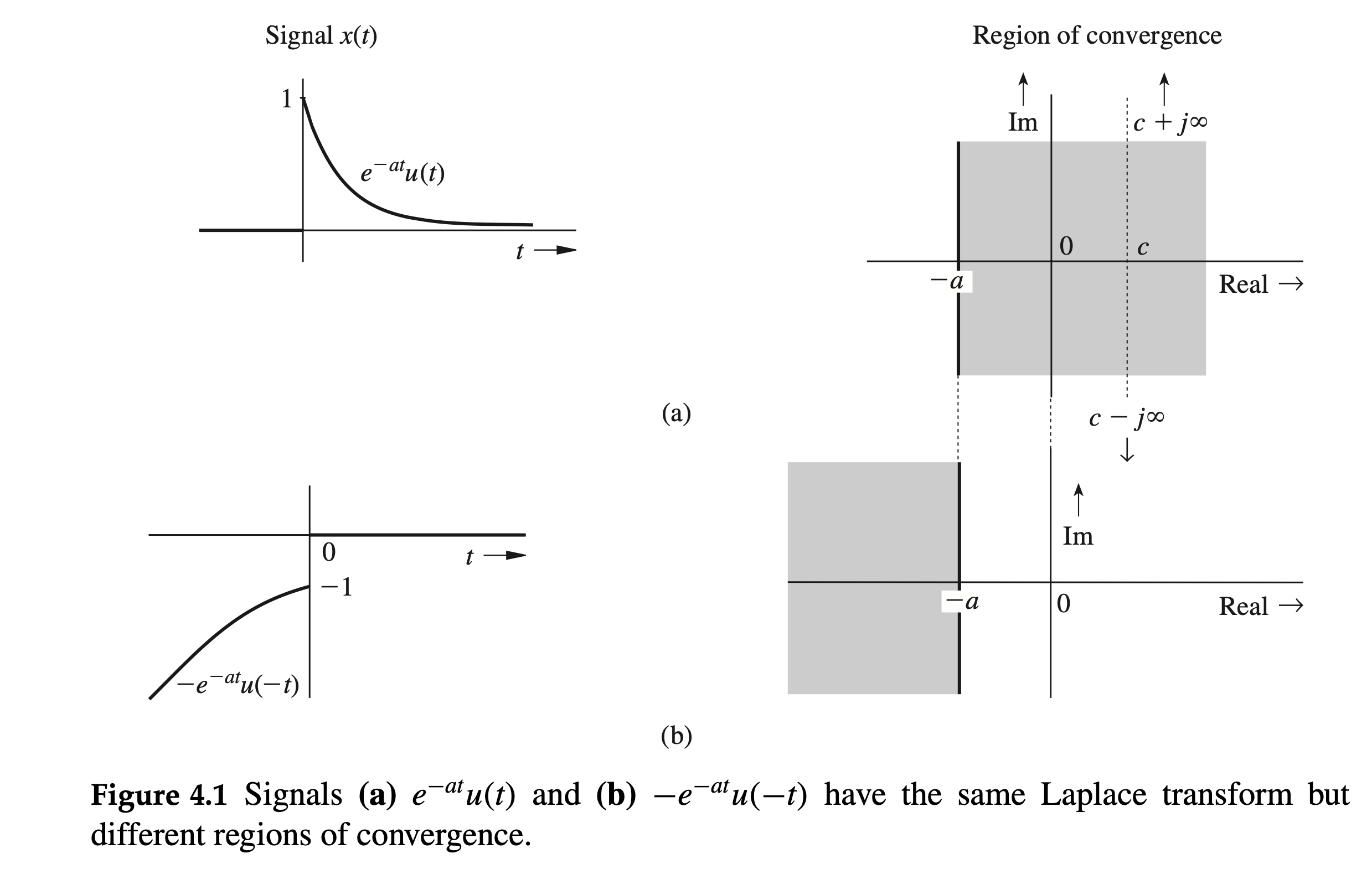

The ROC is \(\operatorname{Re}(s)>-a\), as shown in the shaded region of Fig. 4.1a.

Extension of the Example: A Signal with \(t<0\)

Now consider the signal \(x(t)=-e^{-a t} u(-t)\) illustrated in Fig. 4.1b. Let's find its Laplace transform and ROC.

Solution

The Laplace transform is:

\[ X(s)=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}-e^{-a t} u(-t) e^{-s t} d t \]

Since \(u(-t)=1\) for \(t<0\) and \(u(-t)=0\) for \(t>0\), this becomes:

\[ X(s)=\int_{-\infty}^0-e^{-a t} e^{-s t} d t=-\int_{-\infty}^0 e^{-(s+a) t} d t \]

Evaluating:

\[ X(s)=\left.\frac{1}{s+a} e^{-(s+a) t}\right|_{-\infty} ^0 \]

As \(t \rightarrow-\infty, e^{-(s+a) t} \rightarrow 0\) if \(\operatorname{Re}(s+a)<0\). Thus:

\[ X(s)=\frac{1}{s+a}, \quad \operatorname{Re}(s+a)<0 \]

or equivalently:

\[ x(t) \Longleftrightarrow \frac{1}{s+a}, \quad \operatorname{Re}(s)<-a . \]

The ROC is \(\operatorname{Re}(s)<-a\), as shown in Fig. 4.1b.

Ambiguity of the Inverse Laplace Transform

As demonstrated in the previous example, the inverse Laplace transform is not unique without specifying the ROC. For instance, both \(e^{-a t} u(t)\) and \(-e^{-a t} u(-t)\) share the same transform \(X(s)=\frac{1}{s+a}\), but their ROCs differ. This ambiguity is a significant drawback of the bilateral Laplace transform.

To address this issue, the unilateral Laplace transform was developed, focusing only on the \(t \geq\) 0 portion of signals. This approach ensures a unique inverse transform for a given \(X(s)\).

Unilateral Laplace Transform

The unilateral Laplace transform of a signal \(x(t)\) is defined as: \[ X(s)=\int_{0^{-}}^{\infty} x(t) e^{-s t} d t \]

where \(s\) is a complex variable.

The unilateral Laplace transform is a special case of the bilateral Laplace transform where the signal \(x(t)\) is restricted to \(t \geq 0\). This restriction ensures favorable properties, including a unique inverse transform.

Note: Unless otherwise specified, the term Laplace transform generally refers to the unilateral Laplace transform.

The inverse transform remains the same as in the bilateral case, but due to the restriction on \(t\), the region of convergence (ROC) need not be explicitly specified, as the inverse transform is unique.

Tips

Restricting \(x(t)\) to \(t \geq 0\) can be achieved by multiplying \(x(t)\) with the unit step function \(u(t)\), which is defined as:

\[ u(t)= \begin{cases}1 & \text { if } t \geq 0 \\ 0 & \text { if } t<0\end{cases} \]

Thus, the unilateral Laplace transform of \(x(t)\) can be expressed as:

\[ X(s)=\int_{0^{-}}^{\infty} x(t) e^{-s t} d t=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} x(t) u(t) e^{-s t} d t \]

A detailed explanation involves concepts from complex analysis, which are beyond the scope of this discussion. For simplicity, we omit these details here.↩︎