Tree of Thoughts

- Tree of Thoughts: Deliberate Problem Solving with Large Language Models

- Self-Consistency Improves Chain of Thought Reasoning in Language Models

Intro

Originally designed to generate text, scaled-up versions of language models (LMs) such as GPT [22, 23, 1, 20] and PaLM [5] have been shown to be increasingly capable of performing an ever wider range of tasks requiring mathematical, symbolic, commonsense, and knowledge reasoning.

It is perhaps surprising that underlying all this progress is still the original autoregressive mechanism for generating text, which makes token-level decisions one by one and in a left-to-right fashion.

- Inspiration: In 1950s, Newell and colleagues characterized problem solving [18] as search through a combinatorial problem space, represented as a tree.

- Main idea:

- CoT gives a way of designing prompts to help LMs reson better. However, in CoT, thought sequences are designed to have a chain struture, which means there's only one thought processe for the same problem.

- ToT develops this idea. Make the thought sequences have a tree struture. Given a problem, ToT proposes different "solutions", aka thought processes. In addition, these solutions are well-strutured. So that we can freely use tree-struture algorithms to futher develop this idea.

- The benefits of ToT:

- It's more general, CoT can be treated as a special case of ToT.

- It provides a way to translate classical insights about problem-solving into actionable methods for contemporary LMs.

- It's totally flexible. One can apply ToT to any existing LM. And each component in ToT can be replaced with another.

- Future: Hope for more experiments!

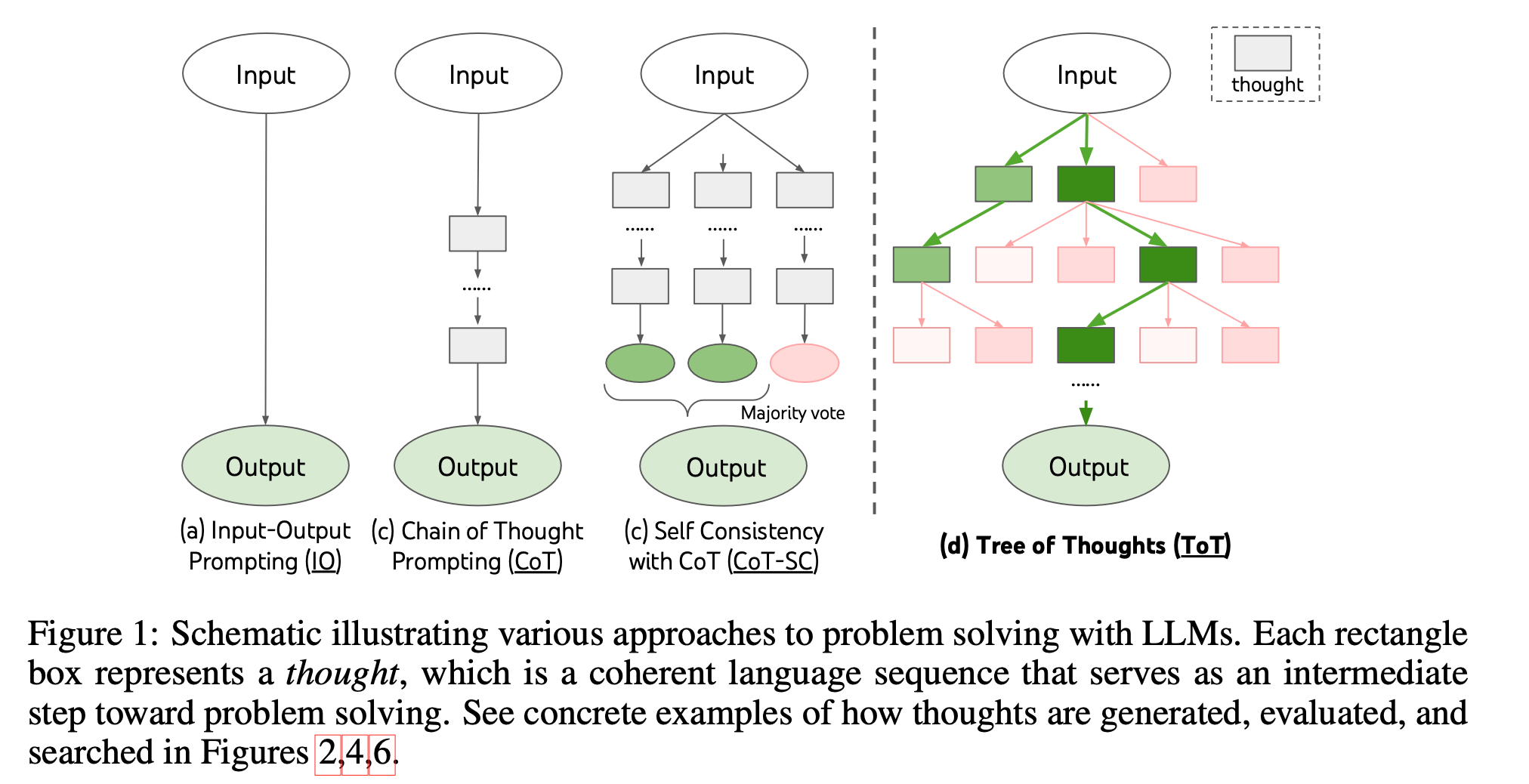

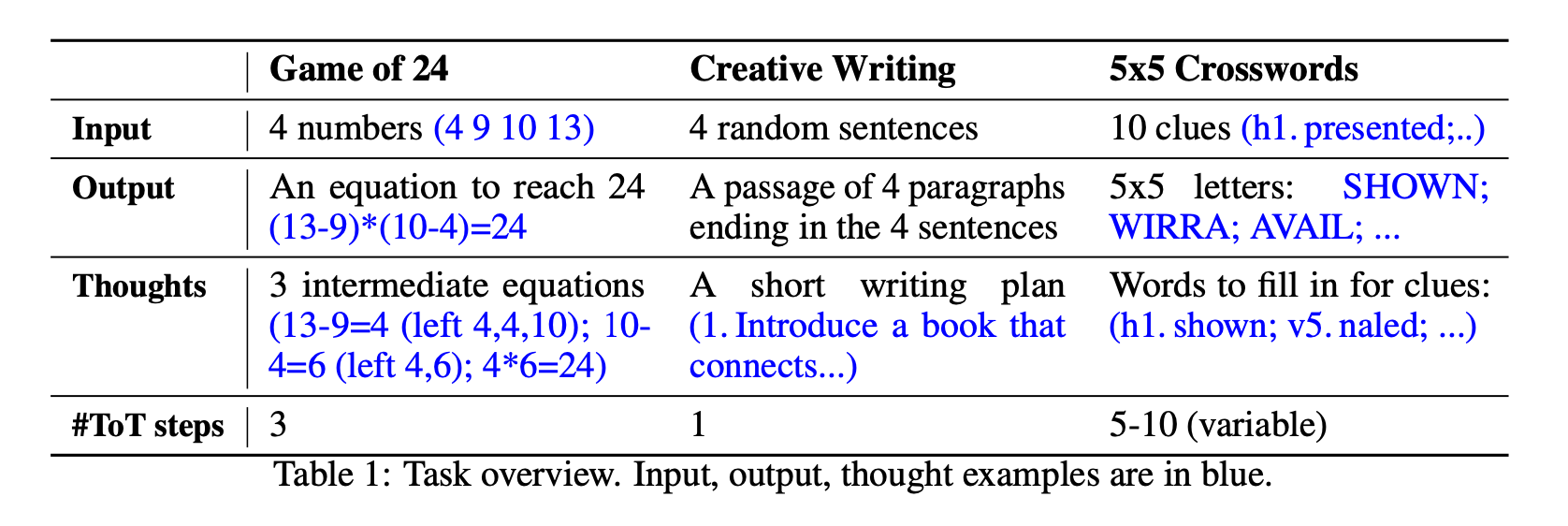

- As Figure 1 illustrates, while existing methods (detailed below) sample continuous language sequences for problem solving, ToT actively maintains a tree of thoughts, where each thought is a coherent language sequence that serves as an intermediate step toward problem solving (Table 1)

Background

First, let's formalize the problem and some existing methods.

We use \(p_\theta\) to denote a pre-trained LM with parameters \(\theta\), and \(x^n, y^n, z^n, s^n, \cdots\) to denote a language sequence, i.e. \(x^n = (x[1], \cdots, x[n])\) where each \(x^n[i]\) is a token, so that \(p_\theta(x^n)=\prod_{i=1}^n p_\theta(x^i)\) (//TODO).

We use uppercase letters \(S, \cdots\) to denote a collection of language sequences.

Input-output (IO) prompting is the most common way to turn a problem input \(x^n\) into output \(y^n\) with LM: \(y^n \sim p_\theta\left(y^n \mid \operatorname{prompt}_{I O}(x^n)\right)\), where \(\operatorname{prompt}_{I O}(x^n)\) wraps input \(x^n\) with task instructions and/or fewshot input-output examples.

For simplicity, let us denote \(p_\theta^{\text {promptMethod }}\) (output \(\mid\) input) \(=p_\theta\) (output \(\mid\) promptMethod(input)), so that IO prompting can be formulated as \(y \sim p_\theta^{I O}(y \mid x^n)\), where "IO" means IO prompting.

Chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting was proposed to address cases where the mapping of input \(x^n\) to output \(y\) is non-trivial (e.g. when \(x^n\) is a math question and \(y\) is the final numerical answer). The key idea is to introduce a chain of thoughts \(z_1, \cdots, z_n\) to bridge \(x^n\) and \(y\), where each \(z_i\) is a coherent language sequence that serves as a meaningful intermediate step toward problem solving (e.g. \(z_i\) could be an intermediate equation for math QA).

To solve problems with CoT, each thought sampled sequentially. We have input \(z_i \sim p_\theta^{C o T}\left(z_i \mid x^n, z_{1 \cdots i-1}\right)\) , output \(y \sim p_\theta^{C o T}\left(y \mid x^n, z^n\right)\).

In practice, \(\left[z^n, y\right] \sim p_\theta^{COT}\left(z^n, y^n \mid x^n\right)\) is sampled as a continuous language sequence, and the decomposition of thoughts (e.g. is each \(z_i\) a phrase, a sentence, or a paragraph) is left ambiguous.

Self-consistency with CoT (CoT-SC) [33] is an ensemble approach that samples \(k\) i.i.d.chains of thought: \(\left[z_{1 \cdots n}^{(i)}, y^{(i)}\right] \sim p_\theta^{C o T}\left(z_{1 \cdots n}, y \mid x^n\right)(i=1 \cdots k)\), then returns the most frequent output: \(\arg \max _y \#\left\{i \mid y^{(i)}=y\right\}\).

CoT-SC improves upon CoT, because it generates different thought processes for the same problem (e.g. different ways to prove the same theorem), and the output decision can be more faithful by exploring a richer set of thoughts. However, within each chain there is no local exploration of different thought steps, and the "most frequent" heuristic only applies when the output space is limited (e.g. multi-choice QA).

Tree of Thoughts (ToT)

ToT frames any problem as a search over a tree, where each node is a state \(s = [x, z^i ]\) representing a partial solution with the input and the sequence of thoughts so far.

A specific instantiation of ToT involves answering four questions:

- How to decompose the intermediate process into thought steps;

- How to generate potential thoughts from each state;

- How to heuristically evaluate states;

- What search algorithm to use.

Step1: Thought decomposition

While CoT samples thoughts coherently without explicit decomposition, ToT leverages problem properties to design and decompose intermediate thought steps.

As Table 1 shows, depending on different problems, a thought could be a couple of words (Crosswords), a line of equation (Game of 24), or a whole paragraph of writing plan (Creative Writing).

In general, a thought should be "small" enough so that LMs can generate promising and diverse samples (e.g. generating a whole book is usually too "big" to be coherent), yet "big" enough so that LMs can evaluate its prospect toward problem solving (e.g. generating one token is usually too "small" to evaluate).

Step2: Thought generator

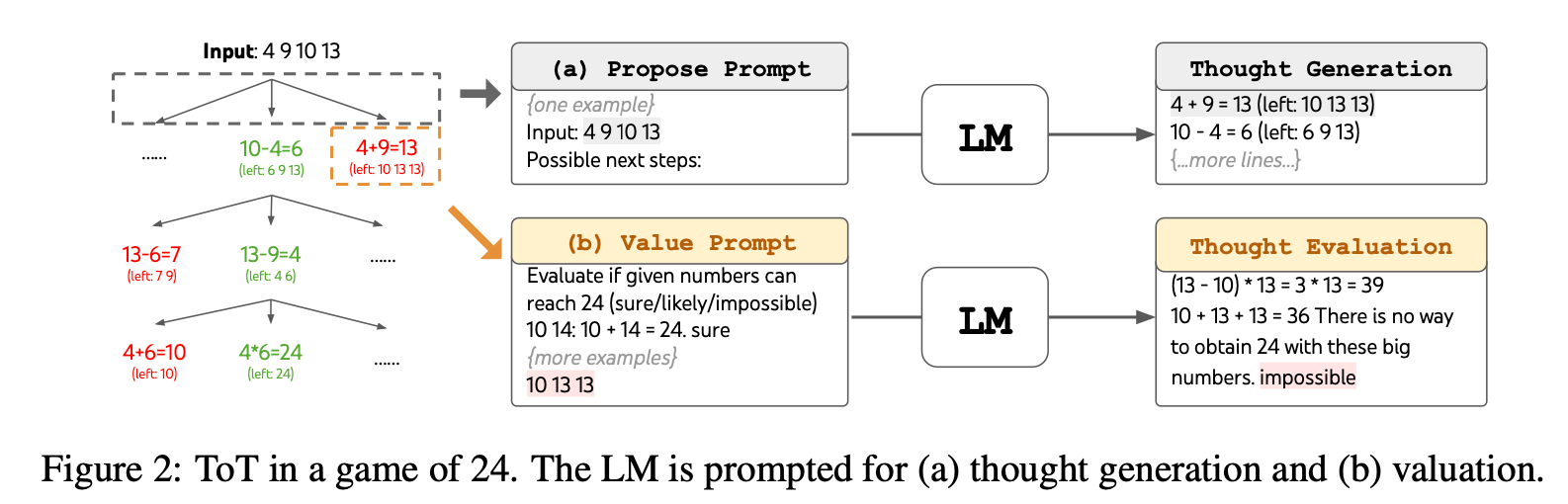

Thought generator \(G\left(p_\theta, s, k\right)\). Given a tree state \(s = [x, z^i ]\), we consider two strategies to generate \(k\) candidates for the next thought step: (a) Sample i.i.d.thoughts from a CoT prompt (Creative Writing, Figure 4): \(z^{(j)} \sim\) \(p_\theta^{C o T}\left(z_{i+1} \mid s\right)=p_\theta^{C o T}\left(z_{i+1} \mid x, z_{1 \cdots i}\right)(j=1 \cdots k)\). This works better when the thought space is rich (e.g. each thought is a paragraph), and i.i.d. samples lead to diversity;

- Propose thoughts sequentially using a "propose prompt" (Game of 24, Figure 2; Crosswords, Figure 6): \(\left[z^{(1)}, \cdots, z^{(k)}\right] \sim p_\theta^{\text {propose }}\left(z_{i+1}^{(1 \cdots k)} \mid s\right)\). This works better when the thought space is more constrained (e.g. each thought is just a word or a line), so proposing different thoughts in the same context avoids duplication.

Step3: State evaluator

State evaluator \(V\left(p_\theta, S\right)\). Given a frontier of different states, the state evaluator evaluates the progress they make towards solving the problem, serving as a heuristic for the search algorithm to determine which states to keep exploring and in which order.

There are typically two ways of heuristics:

- programmed (e.g. DeepBlue [3])

- learned (e.g. AlphaGo [26])

However, we propose a new way: by using the LM to deliberately reason about states.

Our way has two steps:

- Value each state independently: \(V\left(p_\theta, S\right)(s) \sim p_\theta^{\text {value }}(v \mid s) \forall s \in S\), where a value prompt reasons about the state \(s\) to generate a scalar value \(v\) (e.g. 1-10) or a classification (e.g. sure/likely/impossible) that could be heuristically turned into a value.

- Vote across states: \(V\left(p_\theta, S\right)(s)=\mathbb{1}\left[s=s^*\right]\), where a "good" state \(s^* \sim p_\theta^{\text {vote }}\left(s^* \mid S\right)\) is voted out based on deliberately comparing different states in \(S\) in a vote prompt.

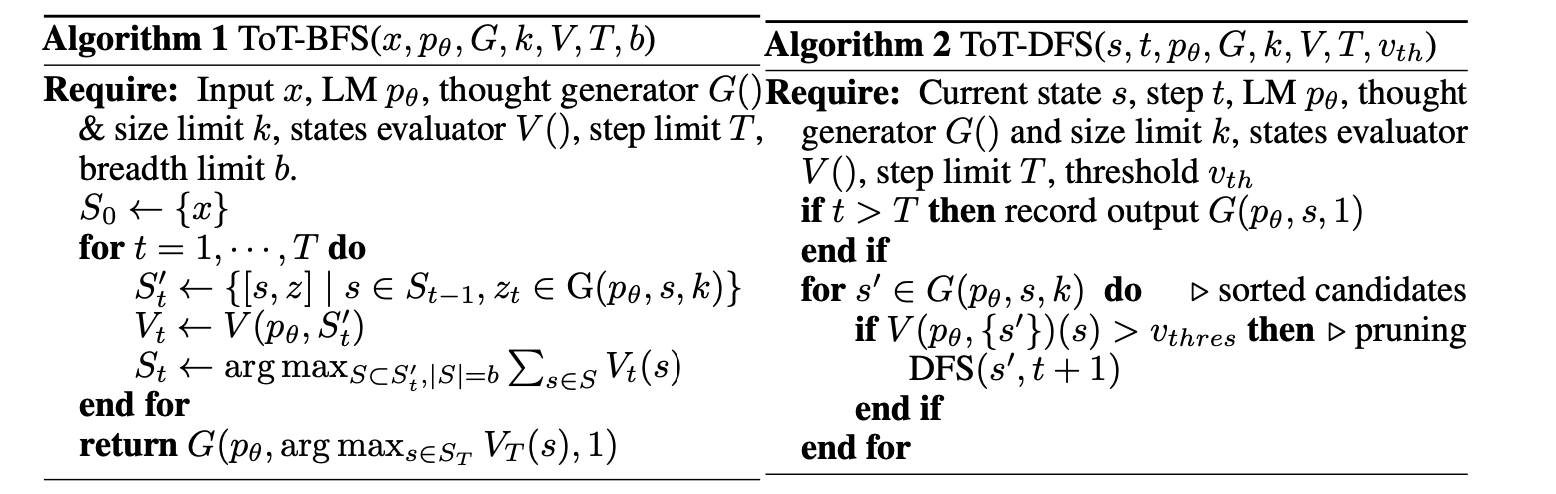

Step4: Search algorithm

We can freely use any tree-struture algorithms, like BFS, DFS, A star, etc.

Experiment: Game of 24

Game of 24 is a math problem, where the goal is to use 4 numbers and basic arithmetic operations (+-*/) to obtain 24.

For example, given input “4 9 10 13”, a solution output could be “(10 - 4) * (13 - 9) = 24”.

Results:

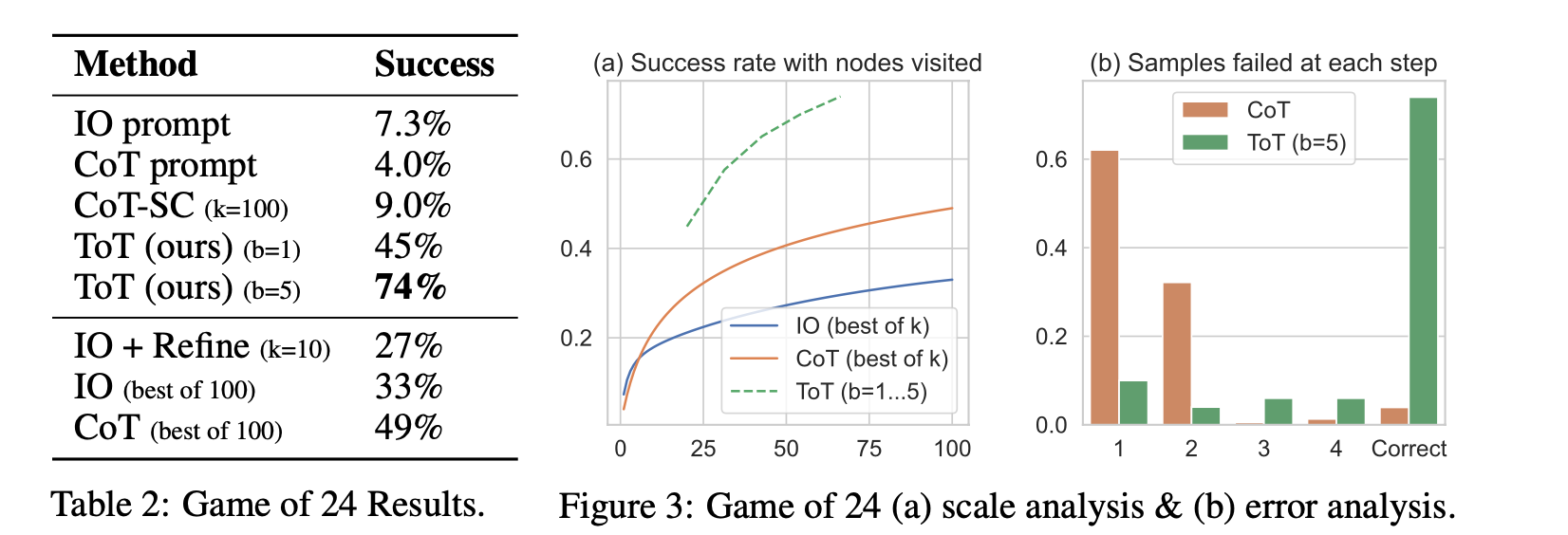

As shown in Table 2, IO, CoT, and CoT-SC prompting methods perform badly on the task, achieving only 7.3%, 4.0%, and 9.0% success rates. In contrast, ToT with a breadth of b = 1 already achieves a success rate of 45%, while b = 5 achieves 74%. We also consider an oracle setup for IO/CoT, by calculating the success rate using best of k samples (1 ≤ k ≤ 100). To compare IO/CoT (best of k) with ToT, we consider calculating the tree nodes visited per task in ToT across b = 1 · · · 5, and map the 5 success rates in Figure 3(a), treating IO/CoT (best of k) as visiting k nodes in a bandit. Not surprisingly, CoT scales better than IO, and best of 100 CoT samples achieve a success rate of 49%, but still much worse than exploring more nodes in ToT (b > 1).