Operations on Relations

Ref: Bernard Kolman, Robert C. Busby & Sharon Cutler Ros. (2014). Relations and Digraph. Discrete Mathematical Structures (6th ed., pp. 139-204). Pearson.

Intro

Now that we have investigated the classification of relations by properties they do or do not have, we next define some operations on relations. Together with these operations, the accompanying properties form a mathematical structure

Let \(R\) and \(S\) be relations from a set \(A\) to a set \(B\).

Since \(R\) and \(S\) are simply subsets of \(A \times B\), we can use set operations on \(R\) and \(S\).

Complement

- complementary relation: \(R\)的补运算\(\bar{R}\)

\[ a \ \bar{R} \ b \quad \iff a\ \not R \ b \text {. } \]

Inverse

- inverse relation: \(R\)的逆运算\({R}^{-1}\)

\[ a \ {R}^{-1} \ b \quad \iff b \ R \ a \text {. } \]

THEOREM 1: R from A to B

Suppose that \(R\) and \(S\) are relations from \(A\) to \(B\). (a) If \(R \subseteq S\), then \(R^{-1} \subseteq S^{-1}\). (b) If \(R \subseteq S\), then \(\bar{S} \subseteq \bar{R}\). (c) \((R \cap S)^{-1}=R^{-1} \cap S^{-1}\) and \((R \cup S)^{-1}=R^{-1} \cup S^{-1}\). (d) \(\overline{R \cap S}=\bar{R} \cup \bar{S}\) and \(\overline{R \cup S}=\bar{R} \cap \bar{S}\).

Parts (b) and (d) are special cases of general set properties. We now prove part (a). Suppose that \(R \subseteq S\) and let \((a, b) \in R^{-1}\). Then \((b, a) \in R\), so \((b, a) \in S\). This, in turn, implies that \((a, b) \in S^{-1}\). Since each element of \(R^{-1}\) is in \(S^{-1}\), we are done.

We next prove part (c). For the first part, suppose that \((a, b) \in(R \cap S)^{-1}\). Then \((b, a) \in R \cap S\), so \((b, a) \in R\) and \((b, a) \in S\). This means that \((a, b) \in R^{-1}\) and \((a, b) \in S^{-1}\), so \((a, b) \in R^{-1} \cap S^{-1}\). The converse containment can be proved by reversing the steps. A similar argument works to show that \((R \cup S)^{-1}=R^{-1} \cup S^{-1}\). The relations \(\bar{R}\) and \(R^{-1}\) can be used to check if \(R\) has the properties of relations that we presented in Section 4. For instance, we saw earlier that \(R\) is symmetric if and only if \(R=R^{-1}\). Here are some other connections between operations on relations and properties of relations.

THEOREM 2: R on A

Let \(R\) and \(S\) be relations on a set \(A\). (a) If \(R\) is reflexive, so is \(R^{-1}\). (b) If \(R\) and \(S\) are reflexive, then so are \(R \cap S\) and \(R \cup S\). (c) \(R\) is reflexive if and only if \(\bar{R}\) is irreflexive.

Proof:

Let \(\Delta\) be the equality relation on \(A\). We know that \(R\) is reflexive if and only if \(\Delta \subseteq R\). Clearly, \(\Delta=\Delta^{-1}\), so if \(\Delta \subseteq R\), then \(\Delta=\Delta^{-1} \subseteq R^{-1}\) by Theorem 1 , so \(R^{-1}\) is also reflexive. This proves part (a). To prove part (b), we note that if \(\Delta \subseteq R\) and \(\Delta \subseteq S\), then \(\Delta \subseteq R \cap S\) and \(\Delta \subseteq R \cup S\). To show part (c), we note that a relation \(S\) is irreflexive if and only if \(S \cap \Delta=\varnothing\). Then \(R\) is reflexive if and only if \(\Delta \subseteq R\) if and only if \(\Delta \cap \bar{R}=\varnothing\) if and only if \(\bar{R}\) is irreflexive.

THEOREM3

Let \(R\) be a relation on a set \(A\). Then (a) \(R\) is symmetric if and only if \(R=R^{-1}\). (b) \(R\) is antisymmetric if and only if \(R \cap R^{-1} \subseteq \Delta\). (c) \(R\) is asymmetric if and only if \(R \cap R^{-1}=\varnothing\).

THEOREM4

Let \(R\) and \(S\) be relations on \(A\). (a) If \(R\) is symmetric, so are \(R^{-1}\) and \(\bar{R}\). (b) If \(R\) and \(S\) are symmetric, so are \(R \cap S\) and \(R \cup S\).

Proof:

If \(R\) is symmetric, \(R=R^{-1}\) and thus \(\left(R^{-1}\right)^{-1}=R=R^{-1}\), which means that \(R^{-1}\) is also symmetric. Also, \((a, b) \in(\bar{R})^{-1}\) if and only if \((b, a) \in \bar{R}\) if and only if \((b, a) \notin R\) if and only if \((a, b) \notin R^{-1}=R\) if and only if \((a, b) \in \bar{R}\), so \(\bar{R}\) is symmetric and part (a) is proved. The proof of part (b) follows immediately from Theorem 1(c).

THEOREM5

Let \(R\) and \(S\) be relations on \(A\). (a) \((R \cap S)^2 \subseteq R^2 \cap S^2\). (b) If \(R\) and \(S\) are transitive, so is \(R \cap S\). (c) If \(R\) and \(S\) are equivalence relations, so is \(R \cap S\).

Proof:

We prove part (a) geometrically. We have \(a(R \cap S)^2 b\) if and only if there is a path of length 2 from \(a\) to \(b\) in \(R \cap S\). Both edges of this path lie in \(R\) and in \(S\), so \(a R^2 b\) and \(a S^2 b\), which implies that \(a\left(R^2 \cap S^2\right) b\). To show part (b), recall from Section 4 that a relation \(T\) is transitive if and only if \(T^2 \subseteq T\). If \(R\) and \(S\) are transitive, then \(R^2 \subseteq R, S^2 \subseteq S\), so \((R \cap S)^2 \subseteq R^2 \cap S^2\) [by part (a)] \(\subseteq R \cap S\), so \(R \cap S\) is transitive. We next prove part (c). Relations \(R\) and \(S\) are each reflexive, symmetric, and transitive. The same properties hold for \(R \cap S\) from Theorems 2(b), 4(b), and 5(b), respectively. Hence \(R \cap S\) is an equivalence relation.

Closure

If \(R\) is a relation on a set \(A\), it may well happen that \(R\) lacks some of the important relational properties, especially reflexivity, symmetry, and transitivity

If \(R\) does not possess a particular property, we may wish to add pairs to \(R\) until we get a relation that does have the required property. 我们很自然地想到可以通过给R添加一些有序对直到它满足题目所给的property.

Naturally, we want to add as few new pairs as possible, so what we need to find is the smallest relation \(R_1\) on \(A\) that contains \(R\) and possesses the property we desire. Sometimes \(R_1\) does not exist. If a relation such as \(R_1\) does exist, we call it the closure of \(R\) with respect to the property in question. 我们要得到的是\(R\)的最小超集\(R_1\), 它具有我们希望的property. 如果\(R_1\)存在, 那么就称\(R_1\)为\(R\)的关于给定property的闭包(closure).

Transtive Closure放在单独的章节讲. 本章介绍Reflexive Closure and Symmetric Closure.

Reflexive Closure

Suppose that \(R\) is a relation on a set \(A\), and \(R\) is not reflexive. This can only occur because some pairs of the diagonal relation \(\Delta\) are not in \(R\).

Thus \(R_1=R \cup \Delta\) is the smallest reflexive relation on \(A\) containing \(R\); that is, the reflexive closure of \(R\) is \(R \cup \Delta\).

Symmetric Closure

Suppose now that \(R\) is a relation on \(A\) that is not symmetric. Then there must exist pairs \((x, y)\) in \(R\) such that \((y, x)\) is not in \(R\).

Of course, \((y, x) \in R^{-1}\), so if \(R\) is to be symmetric we must add all pairs from \(R^{-1}\); that is, we must enlarge \(R\) to \(R \cup R^{-1}\). \(R \cup R^{-1}\)是\(R\)的超集. 这里没有证明\(R \cup R^{-1}\)是“最小的”, 因为这是显然的, 这是由于我们只添加了symmetric所需的必要的有序对,.

Clearly, \(\left(R \cup R^{-1}\right)^{-1}=R \cup R^{-1}\).这里证明了\(R \cup R^{-1}\)也是symmetric的.

So \(R \cup R^{-1}\) is the smallest symmetric relation containing \(R\); that is, \(R \cup R^{-1}\) is the symmetric closure of \(R\).

Example:

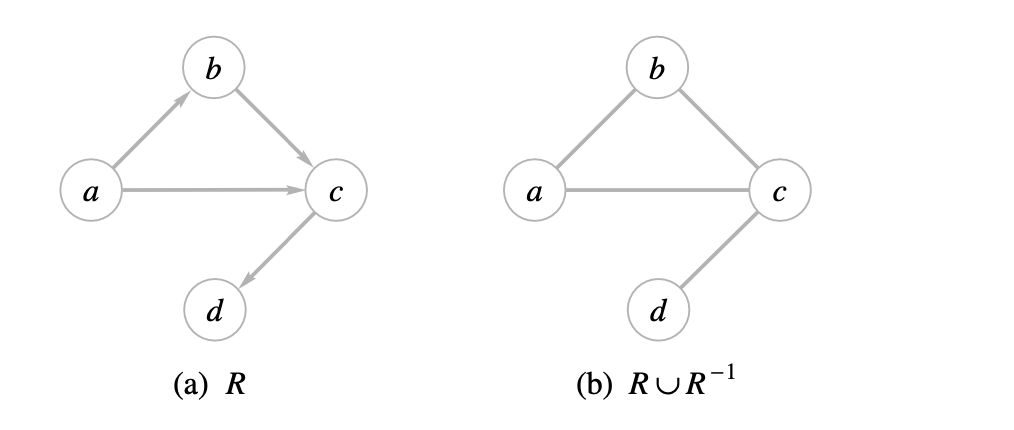

If \(A=\{a, b, c, d\}\) and \(R=\{(a, b),(b, c),(a, c),(c, d)\}\), then \(R^{-1}=\{(b, a)\), \((c, b),(c, a),(d, c)\}\), so the symmetric closure of \(R\) is \[ R \cup R^{-1}=\{(a, b),(b, a),(b, c),(c, b),(a, c),(c, a),(c, d),(d, c)\} . \] The symmetric closure of a relation \(R\) is very easy to visualize geometrically. All edges in the digraph of \(R\) become "two-way streets" in \(R \cup R^{-1}\). Thus the graph of the symmetric closure of \(R\) is simply the digraph of \(R\) with all edges made bidirectional. We show in Figure 39(a) the digraph of the relation \(R\) of Example 9. Figure 39(b) shows the graph of the symmetric closure \(R \cup R^{-1}\).

Composition

Now suppose that \(A, B\), and \(C\) are sets, \(R\) is a relation from \(A\) to \(B\), and \(S\) is a relation from \(B\) to \(C\).

我们可以定义一个新的relation \(S \circ R\), 它是\(R\)和\(S\)的composition(组合).

\(S \circ R\)是一个 \(A\) 到 \(C\) 的关系, 定义如下:

If \(a\) is in \(A\) and \(c\) is in \(C\), then \(a(S \circ R) c\) <=> for some \(b\) in \(B\), we have \(a R b\) and \(b S c\).

\(a(S \circ R) c\) <=>"存在" \(b\), 使得路径\(aRb, bRc\)成立

In other words, \(a\) is related to \(c\) by \(S \circ R\) if we can get from \(a\) to \(c\) in two stages:

- first to an intermediate vertex \(b\) by relation \(R\)

- and then from \(b\) to \(c\) by relation \(S\).

The relation \(S \circ R\) might be thought of as " \(S\) following \(R\) " since it represents the combined effect of two relations, first \(R\), then \(S\).

Example:

Let:

\(A=\{1,2,3,4\}\),

\(R=\{(1,2),(1,1),(1,3),(2,4),(3,2)\}\),

\(S=\{(1,4)\), \((1,3),(2,3),(3,1),(4,1)\}\).

Since \((1,2) \in R\) and \((2,3) \in S\), we must have \((1,3) \in\) \(S \circ R\).

Similarly, since \((1,1) \in R\) and \((1,4) \in S\), we see that \((1,4) \in S \circ R\).

Proceeding in this way, we find that \(S \circ R=\{(1,4),(1,3),(1,1),(2,1),(3,3)\}\). The following result shows how to compute relative sets for the composition of two relations.

THEOREM6

Let \(R\) be a relation from \(A\) to \(B\) and let \(S\) be a relation from \(B\) to \(C\). Then, if \(A_1\) is any subset of \(A\), we have \[ (S \circ R)\left(A_1\right)=S\left(R\left(A_1\right)\right) \] Note: 这里的\((S \circ R)\left(A_1\right)\)表示\(A_1\)的R-相关集, 其中的R在这里指\((S \circ R)\).

Proof: If an element \(z \in C\) is in \((S \circ R)\left(A_1\right)\), then \(x(S \circ R) z\) for some \(x\) in \(A_1\). 对任意一个 \(z \in (S \circ R)\left(A_1\right)\), 自然有\(z \in C\). 根据组合的定义, 总存在\(x \in A_1\)使得\(x(S \circ R) z\) 成立.

根据组合的定义, \(x(S \circ R) z\) 意味着总存在\(y \in B\)使得\(x R y\) and \(y S z\) 成立.

Thus \(y \in R(x)\), \(z \in R(y)\), so \[ \begin{equation}\label{eq1} z \in S(R(x)) \end{equation} \] According to Theorem 1(1) of Relations and Digraphs: If \(A_1 ⊆ A_2\), then \(R(A_1) ⊆ R(A_2)\). Since \(\{x\} \subseteq A_1\), we have \[ S(R(x)) \subseteq S\left(R\left(A_1\right)\right) \] And since \(\eqref{eq1}\), we have \(z \in S\left(R\left(A_1\right)\right)\), so \[ (S \circ R)\left(A_1\right) \subseteq S\left(R\left(A_1\right)\right) \]

Conversely, suppose that \(z \in S\left(R\left(A_1\right)\right)\). Then \(z \in S(y)\) for some \(y\) in \(R\left(A_1\right)\) and, similarly, \(y \in R(x)\) for some \(x\) in \(A_1\). This means that \(x R y\) and \(y S z\), so \(x(S \circ R) z\). Thus \(z \in(S \circ R)\left(A_1\right)\), so \(S\left(R\left(A_1\right)\right) \subseteq(S \circ R)\left(A_1\right)\). This proves the theorem.

THEOREM7

Let \(A, B, C\), and \(D\) be sets, \(R\) a relation from \(A\) to \(B, S\) a relation from \(B\) to \(C\), and \(T\) a relation from \(C\) to \(D\). Then \[ T \circ(S \circ R)=(T \circ S) \circ R . \] Proof The relations \(R, S\), and \(T\) are determined by their Boolean matrices \(\mathbf{M}_R, \mathbf{M}_S\), and \(\mathbf{M}_T\), respectively. As we showed after Example 11, the matrix of the composition is the Boolean matrix product; that is, \(\mathbf{M}_{S \circ R}=\mathbf{M}_R \odot \mathbf{M}_S\). Thus \[ \mathbf{M}_{T \circ(S \circ R)}=\mathbf{M}_{S \circ R} \odot \mathbf{M}_T=\left(\mathbf{M}_R \odot \mathbf{M}_S\right) \odot \mathbf{M}_T . \] Similarly, \[ \mathbf{M}_{(T \circ S) \circ R}=\mathbf{M}_R \odot\left(\mathbf{M}_S \odot \mathbf{M}_T\right) . \] Since Boolean matrix multiplication is associative, we must have \[ \left(\mathbf{M}_R \odot \mathbf{M}_S\right) \odot \mathbf{M}_T=\mathbf{M}_R \odot\left(\mathbf{M}_S \odot \mathbf{M}_T\right), \] and therefore \[ \mathbf{M}_{T \circ(S \circ R)}=\mathbf{M}_{(T \circ S) \circ R} \] Then \[ T \circ(S \circ R)=(T \circ S) \circ R \] since these relations have the same matrices. The proof illustrates the advantage of having several ways to represent a relation. Here using the matrix of the relation produces a simple proof. In general, \(R \circ S \neq S \circ R\), as shown in the following example.