CPU Virtualization in Operation Systems

Sources:

- Remzi H. Arpaci-Dusseau & Andrea C. Arpaci-Dusseau. (2014). Virtualization. Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces (Version 0.8.). Arpaci-Dusseau Books, Inc..

Process

Process is the virtualization of CPU.

The abstraction provided by the OS of a running program is something we will call a process.

Machine states

To understand what constitutes a process, we thus have to understand its machine state: what a program can read or update when it is running. At any given time, what parts of the machine are important to the execution of this program?

Components of a machine state:

Thus the memory that the process can address (called its address space) is part of the process.

Also part of the process’s machine state are registers; many instructions explicitly read or update registers and thus clearly they are important to the execution of the process.

Note that there are some particularly special registers that form part of this machine state. For example, the program counter (PC) (sometimes called the instruction pointer or IP) tells us which instruction of the program is currently being executed; similarly a stack pointer and associated frame pointer are used to manage the stack for function parameters, local variables, and return addresses.

Finally, programs often access persistent storage devices too. Such I/O information might include a list of the files the process currently has open.

Process creation

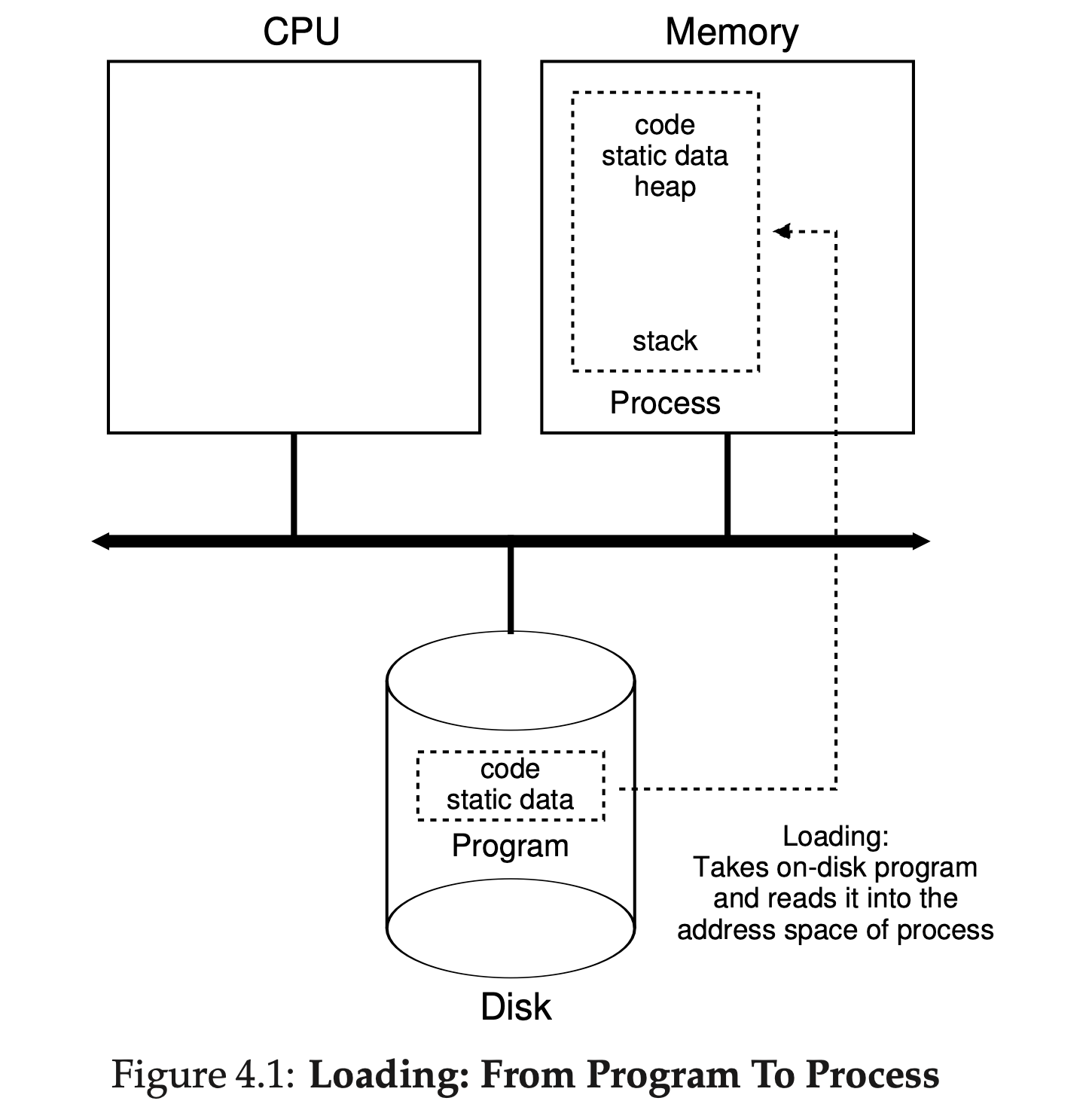

The first thing that the OS must do to run a program is to load its code and any static data (e.g., initialized variables) into memory, into the ad- dress space of the process. Programs initially reside on disk (or, in some modern systems, flash-based SSDs) in some kind of executable format; thus, the process of loading a program and static data into memory requires the OS to read those bytes from disk and place them in memory somewhere (as shown in the following figure).

Once the code and static data are loaded into memory, there are a few other things the OS needs to do before running the process.

Some memory must be allocated for the program’s run-time stack (or just stack). As you should likely already know, C programs use the stack for local variables, function parameters, and return addresses; the OS allocates this memory and gives it to the process. The OS will also likely initialize the stack with arguments; specifically, it will fill in the parameters to the

main()function, i.e.,argcand theargvarray.The OS may also create some initial memory for the program’s heap. In C programs, the heap is used for explicitly requested dynamically allocated data; programs request such space by calling

malloc()and free it explicitly by callingfree().The OS will also do some other initialization tasks, particularly as related to input/output (I/O). For example, in UNIX systems, each process by default has three open file descriptors:

- standard input,

- standard output, and

- standrad error.

These descriptors let programs easily read input from the terminal as well as print output to the screen. We’ll learn more about this later.

By loading the code and static data into memory, by creating and ini- tializing a stack, and by doing other work as related to I/O setup, the OS has now (finally) set the stage for program execution. It thus has one last task: to start the program running at the entry point, namely main(). By jumping to the main() routine (through a specialized mechanism that we will discuss next chapter), the OS transfers control of the CPU to the newly-created process, and thus the program begins its execution.

Process States

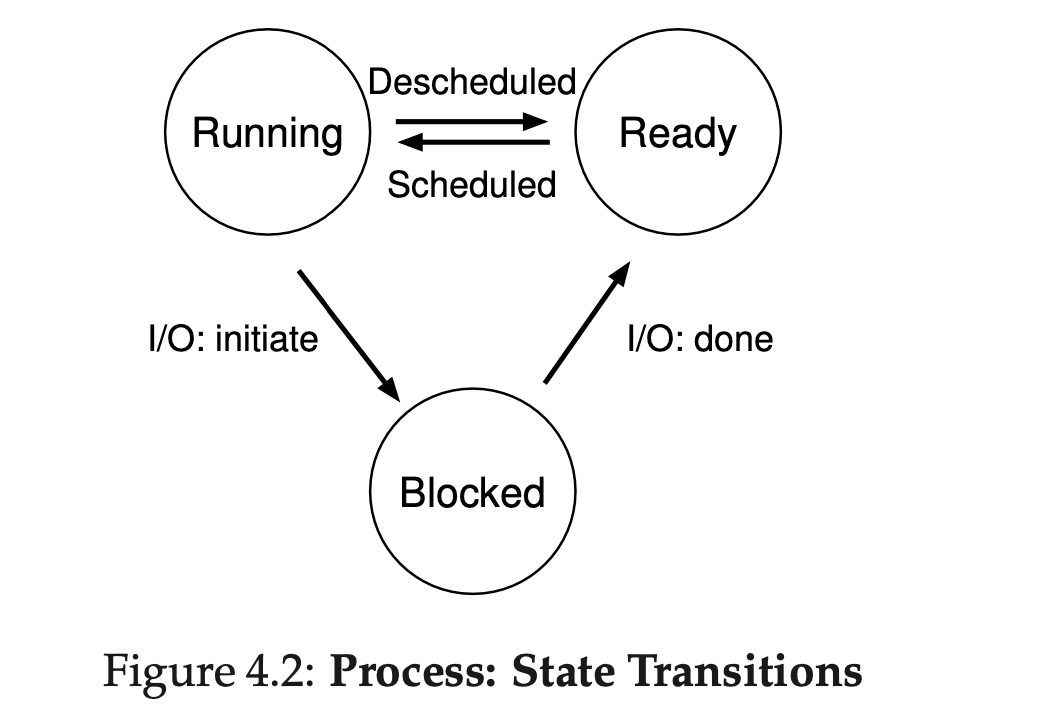

In a simplified view, a process can be in one of three states:

- Running: In the running state, a process is running on a processor. This means it is executing instructions.

- Ready: In the ready state, a process is ready to run but for some reason the OS has chosen not to run it at this given moment.

- Blocked: In the blocked state, a process has performed some kind of operation that makes it not ready to run until some other event takes place. A common example: when a process initiates an I/O request to a disk, it becomes blocked and thus some other process can use the processor.

As you can see in the diagram, a process can be moved between the ready and running states at the discretion of the OS.

- Being moved from ready to running means the process has been scheduled;

- being moved from running to ready means the process has been descheduled.

Linux父进程与子进程在终止时没有相互依赖关系。即爹死了儿子也可以活着, 只是其父进程变为init进程( init 进程是系统的第一个进程,PID=1)

Data Structures

Operating systems are replete with various important data structures that we will discuss.

Process list

To track the state of each process, for example, the OS likely will keep some kind of process list for all processes.

Process structure

From the figure, you can see a couple of important pieces of information the OS tracks about a process. The register context will hold, for a stopped process, the contents of its register state.

1 | // register context |

You can also see from the figure that there are some other states a process can be in, beyond running, ready, and blocked.

Sometimes a system will have an initial state that the process is in when it is being created. Also, a process could be placed in a final state where it has exited but has not yet been cleaned up (in UNIX-based systems, this is called the zombie state1).

This final state can be useful as it allows other processes (usually the parent that created the process) to examine the return code of the process and see if it the just-finished process executed successfully (usually, programs return zero in UNIX-based systems when they have accomplished a task successfully, and non-zero otherwise).

When finished, the parent will make one final call (e.g., wait()) to wait for the completion of the child, and to also indicate to the OS that it can clean up any relevant data structures that referred to the now-extinct process.

Process API

注意,fork()和exec()是分离的,这使得程序可以在fork()之后,exec()之前运行代码,最典型的例子是shell的workflow,参见Using Shell

fork()

1 | //5_1.c |

1 | hello world (pid: 5951) |

fork()创建进程子进程不会从

main()开始执行,而是从fork()处返回,就像它自己调用了fork()子进程几乎完全拷贝了父进程,拥有和父进程相同的地址空间,寄存器,PC等,但它从

fork()获得的返回值不同fork()返回值:ERRORS: -1

子进程: 0

父进程: 新创建的子进程的PID

wait()

1 | //5_2.c |

1 | hello world (pid: 6747) |

wait()会在子进程运行结束后才返回- 如果父进程先运行,它会马上调用

wait()

exec()

1 | //5_3.c |

1 | hello world (pid: 7615) |

exec(): replaces the current process image with a new process imag. 将当前进程的内容替换为不同的程序(wc)

- 对

exec()的成功调用永远不会返回,因为子进程的内容是新的程序 execvp(const char *file, char *const argv[]): one ofexec()family- The initial argument for these functions is the name of a file that is to be executed.

- The char *const argv[] argument is an array of pointers to null-terminated strings that represent the argument list available to the new program. The first argument, by convention, should point to the filename associated with the file being executed. The array of pointers must be terminated by a null pointer.( 因此有

arg[2] = NULL)

Shell

fork()和exec()分离, 使得程序可以在fork()之后,exec()之前运行代码.

Limited directed execution

OS首先(在启动时)设置trap table并开启时钟中断 (都是特权操作),然后仅在受限模式下运行进程。 只在执行特权操作,或者当进程需要切换时,才需要OS干预

OS重获CPU控制权

如果一个进程在CPU上运行,那么OS无法运行。 因此OS需要重获CPU的控制权 * 等待系统调用: 进程通过syscall主动放弃CPU, 比如yield * 时钟中断: 时钟设备可以产生中断,产生中断时,当前进程停止,OS中的 interrupt handler运行,此时OS重获CPU控制权 * 硬件在发生中断时需要为当前进程保存状态

context switch

上下文切换( context switch): OS获得控制权后,需要觉得是否切换进程,如果要切换,那么需要上下文切换 * OS为当前进程保存状态,并为即将执行的进程恢复状态 * "状态": 寄存器,在该进程的内核栈中 * 事实上,除了寄存器,cache, TLB和其他硬件的状态也被切换,因此context switch的成本可能非常高昂 * 本质上是为了确保最后从陷阱返回时,不是返回到之前运行的进程,而是继续执行另一个进程

Syscall

- 我们对系统调用的调用,实际上是对C lib中对应函数的函数调用,这些函数遵循了内核的调用约定(如将参数推到栈,执行

TRAP,返回控制权等)实现了系统调用。 当然,这些C lib中的函数是汇编写的

Interruption

在指令执行周期最后增加一个微操作,以响应中断,CPU在完成执行阶段后,如果允许中断,则进入中断阶段

中断处理过程:

- 保护CPU状态

- 分析被中断进程的PSW中断码字段,识别中断源

- 分别处理发生的中断事件

Thread Scheduling

详见OS Thread Sheduling Algorithm